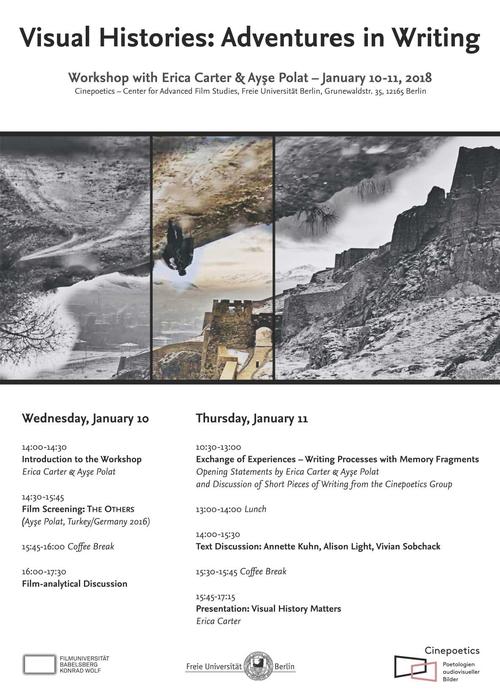

Visual Histories. Adventures in Writing

10./11.01.2018 | Workshop by the Cinepoetics group with Ayse Polat and Erica Carter.

With Ayşe Polat working on a new film and Erica Carter starting an autobiographical endeavor into film and history in the light of colonialism, the workshop was laid out as a highly creative encounter between the two Cinepoetics fellows. "Visual Histories. Adventures in Writing" addressed questions of historicity by considering the process of writing. Specifically, it asked how historical figures – persons, objects or events that may be either fictional or 'authentically' historical – come into being through the writing process. Particular emphasis was put on writing that proceeds on the basis of fragmentary evidence from moving images and the visual archive.

Also, the relation of distance and closeness in regard to (cultural) memory became an important factor in the discussion following the screening of Polat's latest film The Others (2016). Following a bon mot by William Faulkner, "the past is never dead, it is not even past," the film brings together the cultural heritage of Turkish, Kurdish, and Armenian people in the region of Van, Turkey. As the discussants found out, each protagonist's story has an aesthetic rather than an informational content. Historical sights are often in a state of decay but it is in the telling of stories that history finds its resonance. Yet, it would go unnoticed if there wasn't the intimacy of a cinematic perspective on these stories and people that directly connects to Ayşe Polat's autobiographical background.

Channeling Frank Ankersmit's book "Sublime Historical Experience," which the group had read in the Cinepoetics Colloquium, the discussion focused on the surface of language that is revealed through historical experience. In Polat's film, this experience is closely linked to phenomena of rhythm and tone as well as what remains unsaid. Other points that were brought up on the following day were questions of presence, performance, and narration of history.

Keeping these notions in mind, the second day started with an exercise in creative writing. Each participant had prepared a short piece of writing in which they engaged with an image, an artefact, a film fragment, or an archive document. These personal and diverse texts produced an account both faithful to the historicity of the original and making the object 'live' in present time. The following discussion of these poems, fragments, and short essays revolved around questions of form and subjectivity. They brought to light an existential dimension of history, as felt subjectivity and an autobiographical background often clash with scientific 'objectivity' in the realm of history.

It is the textual form but also the forms of time, the 'where' and 'when' of narration, that illuminate accounts of historical experience. In addition, the question of the 'who' became important since there are a multitude of perspectives on the performance of historical accounts. This included a reflection on notions of body and affect clearly at work not only in the performance but also in the reception of historical experience. As comprehension of the 'when' and 'where' becomes cloudy in historical experience, a heightened focus on different affective dimensions is of great importance.

After lunch, the participants engaged in discussion of two texts - Annette Kuhn's "Family Secrets: an Introduction" (2002) and Vivian Sobchack's "A Leg to Stand On: Prosthetics, Metaphor, and Materiality" (2006). Both texts offered valuable insights into autobiographical accounts of historical experience. While Kuhn concentrates on the notion of memory work as the staging of memory that always relates to a certain 'place' (as opposed to a much more loosely defined 'space'), Sobchack takes a different approach. For her, the violence of language as well as its materiality make apparent what defines historical experience. With this, Sobchack also draws attention to the role of the body: there has to be a body to experience memory, otherwise it would just be a bad metaphor for history.

In the closing session, Erica Carter presented a piece on Béla Balázs' historical mode of writing in his book "Der sichtbare Mensch" (1924). His expressionist/modernist style as well as his accounts on the 'gesturology' of Asta Nielsen as a new way of expression led to a discussion on the importance of 'ekphrasis.' This Greek term describes a work of art as a rhetorical exercise, as an intermediary mode of writing between image and language. Erica Carter's presentation aimed at a point where the act of writing history is able to engage in ekphrasis. This would strengthen the notion of historicity explored by the participants of the workshop, as it includes a sense of temporality (rhythm and movement), contingency, and intersubjectivity (which also alludes to affective dimensions of history).