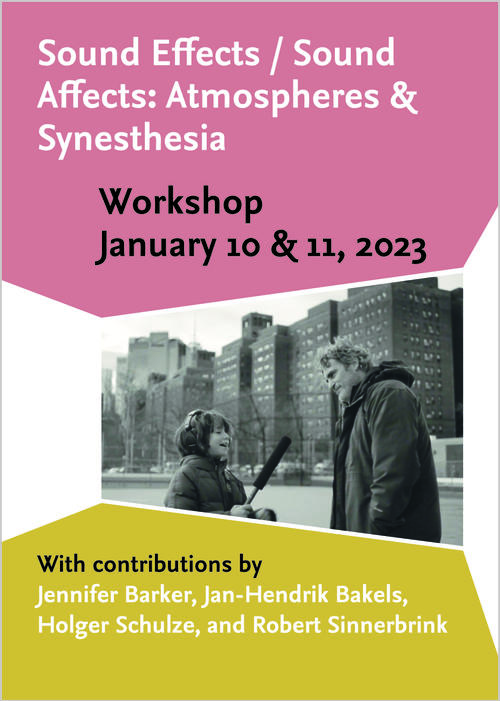

Sound Effects / Sound Affects: Atmospheres & Synesthesia

10. & 11.01.2023 | Workshop der Kolleg-Forschungsgruppe Cinepoetics mit Jennifer Barker, Jan-Hendrik Bakels, Holger Schulze und Robert Sinnerbrink.

Research Focus: Audiovisual Cultures II: Phenomenology of the Anthropocene

As the field of sound studies encompasses a wide array of disciplines, the first day of the workshop began with a short discussion of each participant’s individual methodology. This glimpse into their respective perspective was guided by the principle to approach the Anthropocene through an embodied film experience and spatio-temporal patterns of making-sense within the field of sound studies.

Afterwards, the group watched C’MON C’MON (US 2022), a shared point of reference for each of the four presentations. Day one of the workshop ended with an in-depth discussion of Mike Mills’ film. The group identified it along the lines of an emotional weather report of the present-day US. Its sound design allows for an audible zooming-in and out of perceptual processes. The pacing of the film encourages a different sense of temporality – much like the audio recordings of the protagonist themselves. This experience has been described as a layering of sheets of the past.

The second day of the workshop consisted of four talks with corresponding discussions as well as a final discussion in the evening. Jennifer Barker’s presentation “The Soundtrack of Silence” set out to define a phenomenologically grounded approach to analyse deafness in film. In her talk, she defined four tropes in the staging of deafness that deviate from the omnipresent high-pitched, tinnitus-like buzzing. As such, deafness in film might be noisy, a multi-sensual being-in-the-world as well as groovy and, lastly, occur as a time-image in the Deleuzian sense. Although phenomenology is a suitable perspective for analysing deafness in film, one must clear off the radical relatedness on a unified, able-bodied self, as Barker concluded.

Subsequently, Holger Schulze gave an insight into his work and what it means to think sonically. His presentation, “From Sonic Traces to Sonic Fiction: How Sonic Persona is Staged within a Cinematic Experience,” related scenes from C’MON C’MON to the (ongoing) fabrication of a Sonic Persona. This means, as Schulze explained, highlighting the situatedness of the sonic experience while following a decidedly non-essentialist approach to subjectivity. Thus, the Sonic Persona must be thought of as being “made out of a sensory corpus struggling with changing auditory dispositifs.” However, Schulze stated, sonic is not to be confused with acoustic.

After a short lunch break, the workshop continued with a talk by Jan-Hendrik Bakels: “Sounds Like You’re There. Sound and Audio-Visual Experiences of Presence.” Focusing on the feeling of presence rather than the ontological framework of this notion, Bakels described an affective space of the sensible subject with music and sound foregrounding the encompassing film world. An example of this might be found in the “audio close-up” in the beginning of C’MON C’MON. Via an ASMR-style heightened sensibility, one is being placed within the audio-visual world by a sound design that highlights different sounds. Augmented by the topic of audio recording, this staging of sound leads to a perception of pastness as it is unfolding as presentness, Bakels concluded.

The last presentation of the day was given by Robert Sinnerbrink. Drawing on a vast body of theoretical perspectives, his talk “’There the Colours, Sensations and Sounds Will Wash Over You…’: Sound, World, and Narration in C’MON C’MON” contextualized Mike Mills’ film in yet another way. To analyse this film’s multidimensional world, it is essential to concentrate on the soundscape. Thus, Sinnerbrink proposed to understand atmosphere as a relational expression of ‘spatialized feelings’ that links self and world. The use of sound in C’MON C’MON underlines that ‘emotion’ might not just be understood as a subjectively experienced response to external stimuli, but as an embodied mode of engaging with the affordances of one’s environment.

Following the film’s aesthetic, one must, as Sinnerbrink stated, look beyond the ‘vococentric’ construal of sound and voice as subordinate to narrative representation. These questions of representation and audio-visual staging then segued into the closing discussion, which linked every speaker’s findings to the film discussion from the day before.